Aging Out of Evidence: Why Cancer Trials Still Miss Older Adults

There is a need for trials mirroring real-world practices.

In the Journal of the American Geriatric Society, we recently published, with Vinay Prasad, a paper describing age differences, over more than 20 years, between patients enrolled in clinical trials and those treated outside clinical trials (full paper is available here).

The efficacy-effectiveness gap

An important difference must be made upfront between “efficacy”: what is seen in randomized trials, and “effectiveness”, i.e. what will happen in the real-life settings. Often, a difference will be observed between those two, which is called the "efficacy-effectiveness gap”.

What is an explanation for the difference? Simple - because patients in trials are different from those encountered outside them, and this is problematic.

Age as a key driver of this gap

Part of the mismatch is due to differences in age and health status between trial participants and the general population with the respective condition. The need for better age representation is especially important in oncology, where the risk of cancer increases as people age, yet exclusion criteria related to health conditions often prohibit older people from clinical trial participation, even though they may commonly be treated with the drug in clinical practice.

The observation that clinical trials enroll younger and healthier individuals than in the general population with a given condition is not new, and in fact, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued guidance documents on several occasions to encourage trialists to include a study population that is more representative of the population with a condition. However, differences in age between clinical trials and the real-world may still persist, which is why we set out to assess any potential differences.

Our study - covering more than 20 years of registration trials

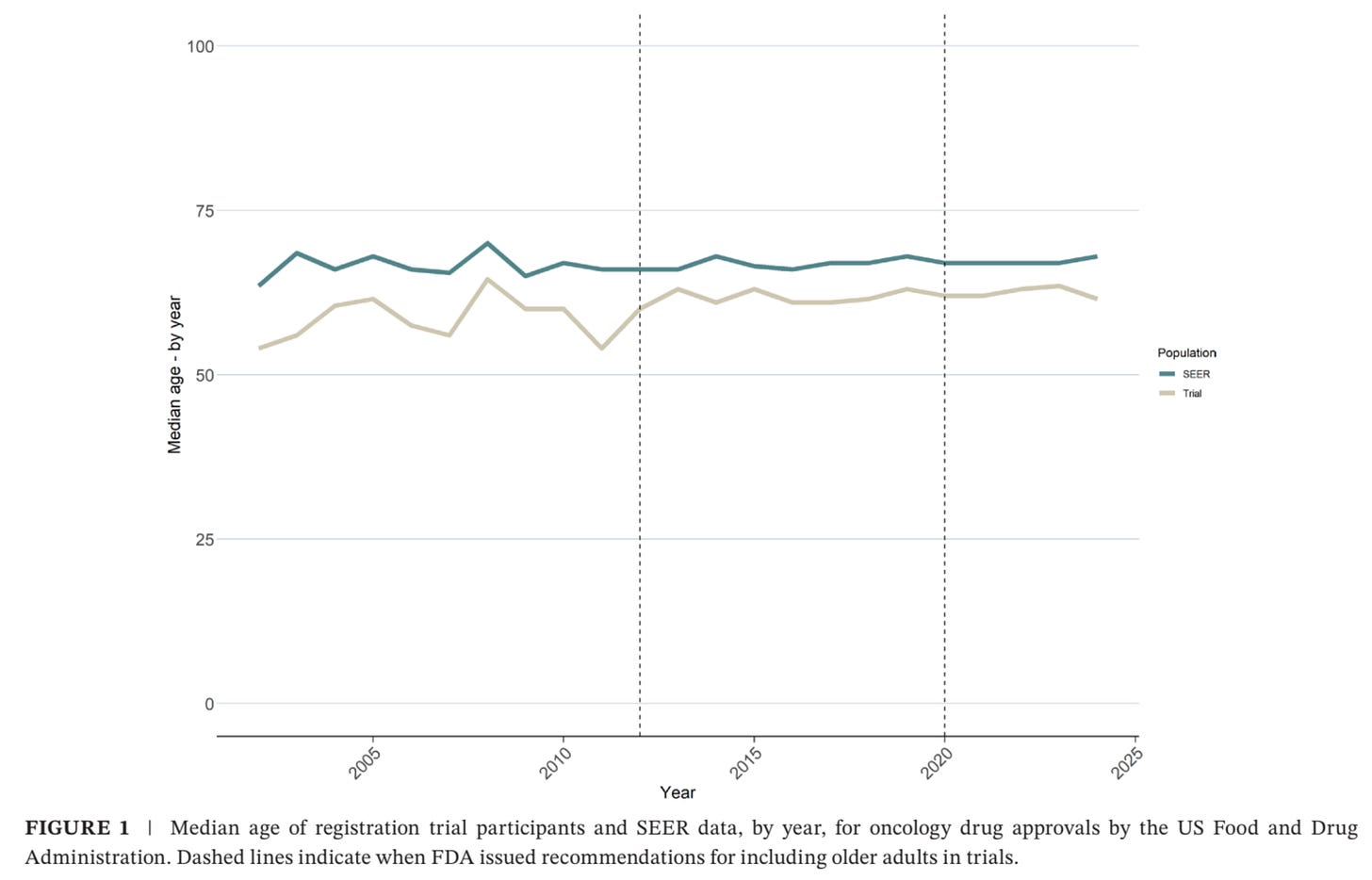

To answer this question, we searched for the age of trial participants and tumor types for all drug approvals going as far back as 2002. We noted multiple metrics of the age of trial participants, including median age and the percentage of people above certain age thresholds (>65 years, >75 years, etc.). To get at the real-world age for each tumor type, we used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for the tumor type being tested in the registration trials for each approval.

The median age of the general population (as per SEER data) was 67 years of age, and the median age of the trial participants was 62 years of age.

We found that the age gap between registration trials and SEER data has declined over time (7 years during 2002-2012 vs 5 years during 2013-2019 vs 4 years during 2020-2024), but the age gap still persists. SEER ages were older than clinical trial ages for all tumor types except for thyroid and leukemia.

How to improve upon those findings?

One possible solution is to conduct trials specifically in older adults. In our review of trials, we found only 5 trials (of 495 non-pediatric trials) that restricted the inclusion criteria to older adults. Of those, 2 used a cut-point of 55 years of age - an age that is not typically considered as “older”.

Limiting the exclusion criteria in a trial may also be a way to get a more representative population. While comorbidities (often occurring as exclusion criteria) in the study population may complicate the interpretation of study findings, they are also more common as people age. Allowing individuals with comorbidities, unless there is a specific reason to exclude them from trial participation, would not only result in a more representative population, it would provide more realistic information on safety and benefit in the context of conditions and medications that older adults commonly have and take.

In conclusion, while there has been progress on shrinking the age gap between clinical trials and the real world population, there is still room for improvement.

Check out the full paper here!

Note for readers: the work presented in this post was prepared prior to my employment at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the views expressed here don't represent the views of the FDA.