Is optimal treatment duration in cancer mostly arbitrary?

A hint: most cancer treatment durations are multiples of years.

In a recent study, out in the European Journal of Cancer, we showed that in most cases, the duration of treatment is not supported by a sound scientific rationale.

Why does the duration of cancer treatment matter?

The duration of cancer treatment is a crucial issue. If it’s too short, the therapy may not achieve its intended benefit. If given for too long, patients may face unnecessary toxicity, poorer quality of life, and higher costs – without added gains. Despite its importance, the optimal duration is rarely studied.

Our study

In our work, we systematically reviewed 227 FDA registration trials (2019–2024). We abstracted information from FDA approval documents and landmark publications, and examined whether trials used fixed or indefinite treatment durations, the clinical setting (advanced, frontline, perioperative), and, crucially, the planned duration versus the actual duration received by patients.

Most durations appear arbitrary

We found that:

60% of trials were planned for an indefinite duration, 40% for a fixed duration.

However, the median duration patients actually received was about 7 months whether the trial was fixed or indefinite!

Across 227 trials, none directly randomized patients to different durations.

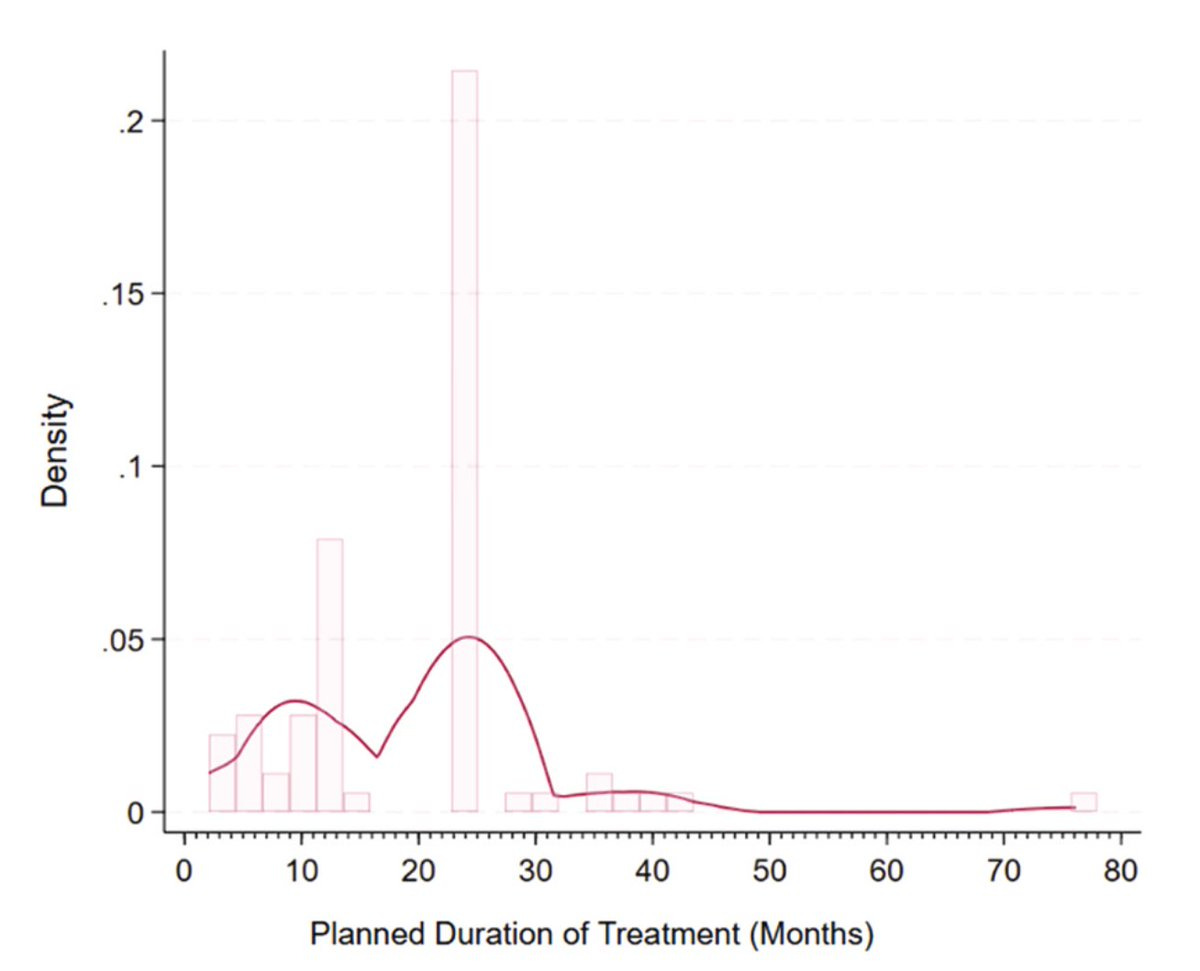

Among fixed trials, 71% were planned for 1 or 2 years (see the 2 "peaks" on the figure below)

This suggests that current durations may largely be arbitrary, calendar-driven choices rather than firmly based on biology or patient needs. On Mercury, where a year lasts only 3 months, those trials might have been multiples of 3 months instead of years!

Why choose “years”? And not “months” or “weeks”?

The simple – yet most likely correct – answer is that longer therapy means more revenue for companies, which currently have little to no incentives to investigate whether shorter course therapy would yield similar gains.

Among the solutions, alternative remuneration models where revenues would be decoupled from drug volume should be considered.

Concluding points

Our study focused on trials leading to marketing authorisations (approvals). Thankfully, there are attempts to study the optimal duration outside those.

However, a key issue is that once a first trial "sets the time", showing non-inferiority for a shorter duration later becomes very challenging, mainly for methodological reasons (see the excellent "The tyranny of non-inferiority trials" paper from Ian Tannock et al.).

Take-home message: regulators and trialists should start by testing shorter durations first, unless there is a strong rationale for longer treatment, and only extend afterwards if there’s clear evidence that longer is better.

Check-out the full paper for more insights!

Love these posts. Thank you!

Very interesting work! I'm curious - what is that outlier drug all the way at around 77 months? I wonder what the median treatment time for that drug was...