Placebo First, Treatment Later: Is This Fair to Patients With Active Cancer?

In a new paper, we examined the randomized trials using inert control arms (mostly placebo only) leading to FDA approvals.

In our new paper, out in the European Journal of Cancer and openly accessible here, we took a close look at randomized trials using inert control arms.

In many trials, placebo are used as add-on to a backbone therapy, trying to isolate the experimental add-on therapy. For instance, you will have trials comparing “chemo + immuno” versus “chemo + placebo”. In our work, we did not include those, we focused on trials where the control arm is “only” an inert compound.

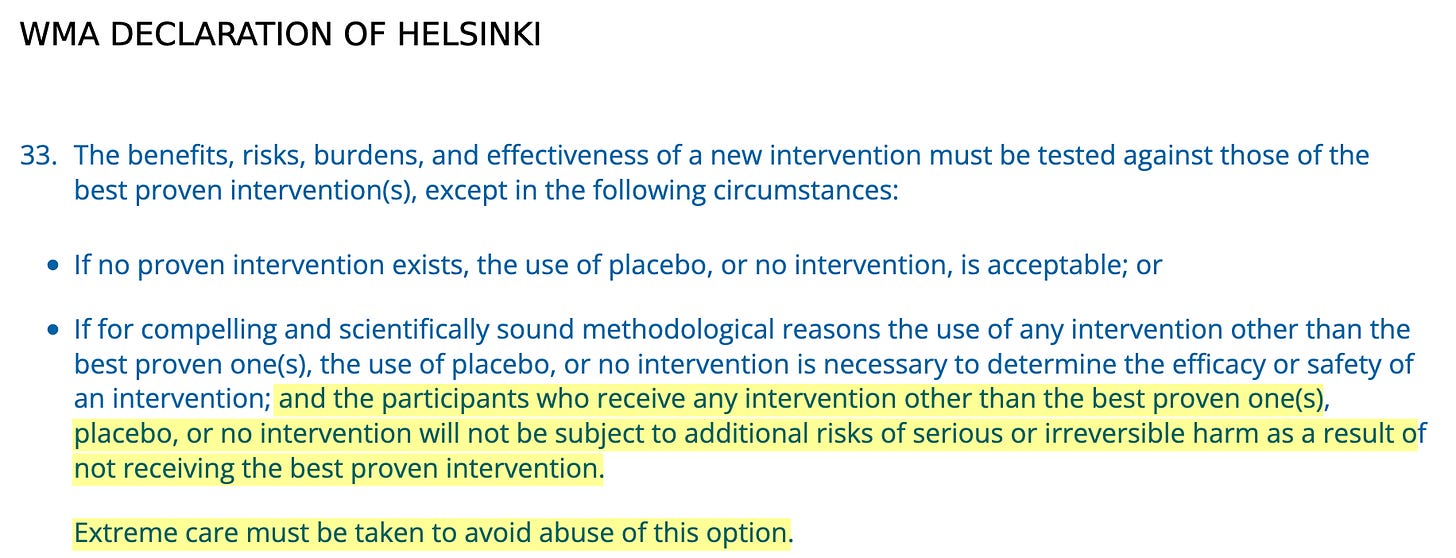

An Ethical Framework for the Use of Placebo

The World Medical Association, in the Helsinki Declaration, describes the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. And when it comes to the control arm and the use of placebo, the declaration is very clear:

“participants (…) will not be subject to additional risks of serious or irreversible harm as a result of not receiving the best-proven intervention.”

Wisely, they add:

“Extreme care must be taken to avoid abuse of this option.”

Does progression or death constitute “irreversible harm”?

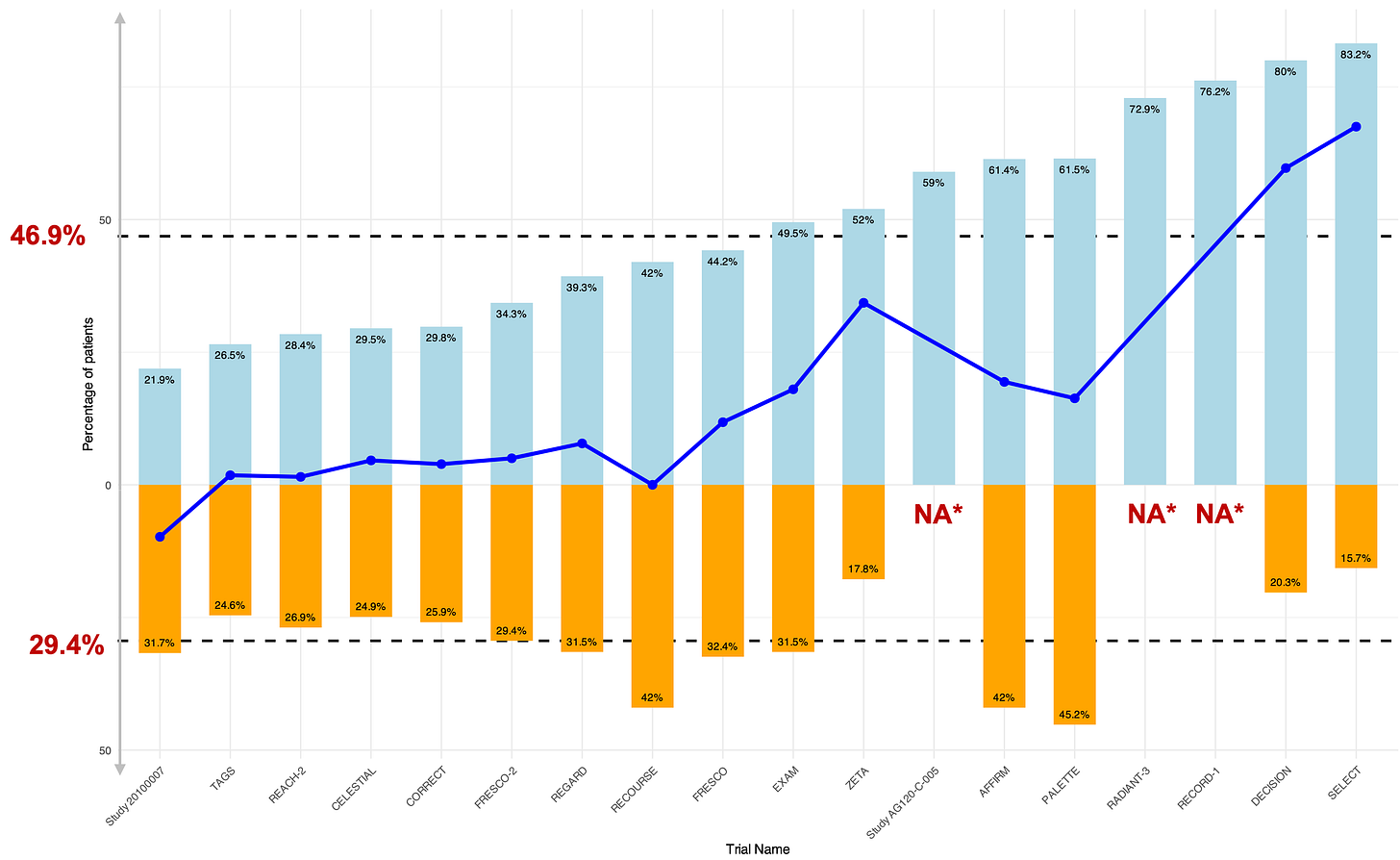

In our work, we looked at FDA approvals over almost 16 years (2009 to November 2024) and found 19 registration randomized trials in the advanced or metastatic setting using such inert control arm. One was excluded from our final analysis as it didn’t report subsequent therapy, leaving 18 trials, most using placebo-only (17 trials) while one was using “best supportive care”.

We used a simple and powerful proxy: how many patients received a subsequent active therapy after receiving an inert control arm?

We found that overall 49% of control patients got subsequent therapy!

In other words, those patients, with advanced or metastatic cancer, were randomized to an inert substance and later, upon progression, finally received an active therapy, including potentially life-prolonging compounds.

Below are the 18 trials with, in blue, the proportion of control arm patients receiving subsequent therapy (and in orange those from the experimental therapy).

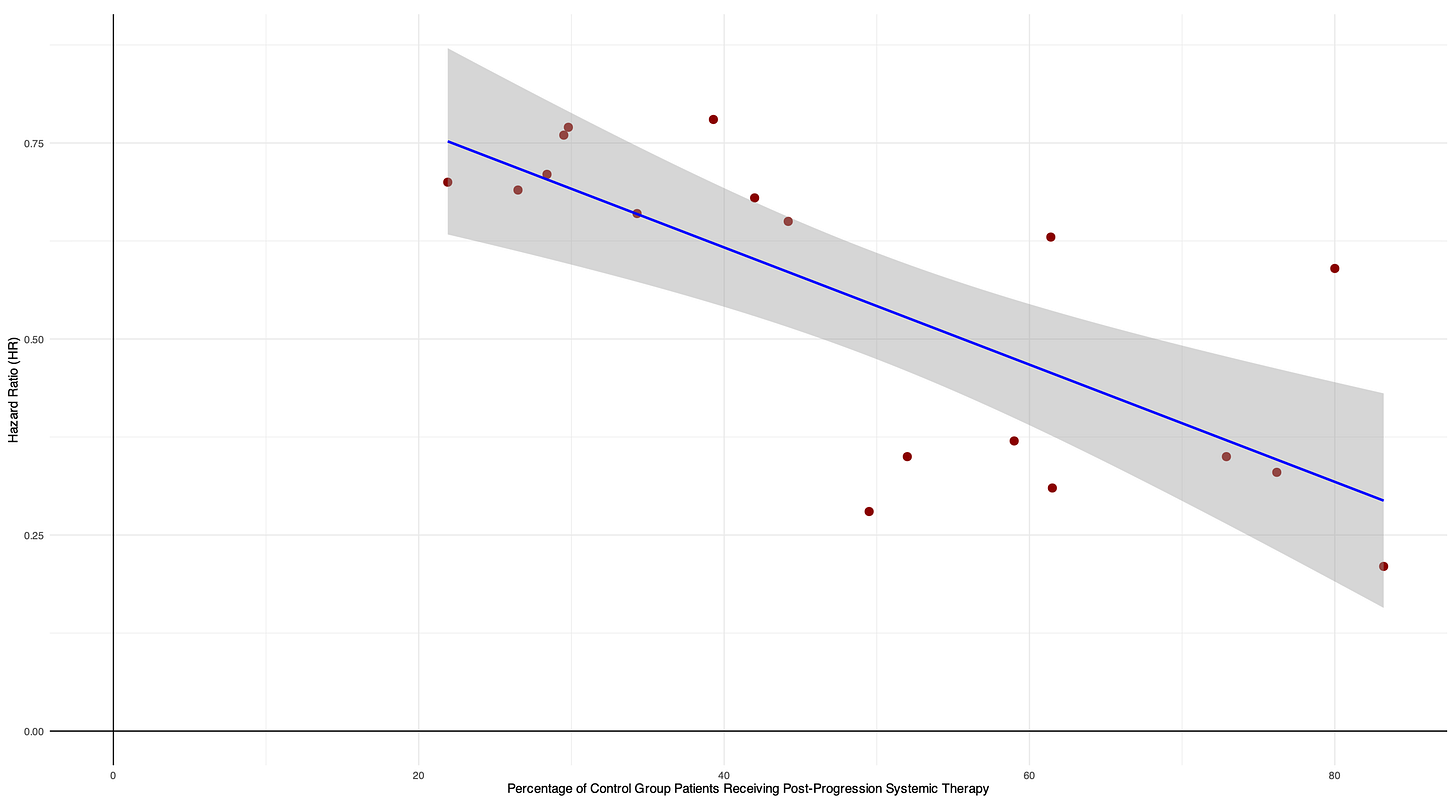

The more subsequent therapy in controls, the higher the “benefit” from the novel therapy.

It is logical that if more patients received subsequent therapy, this indicates that they were more likely eligible for an active therapy upfront rather than an inert control arm. Thus, a high rate of subsequent therapy suggests that a large proportion of patients were genuinely deprived of potentially effective treatment during the randomized phase.

Consistent with this, we found a significant inverse association, with a 0.07 decrease in the hazard ratio (indicating greater magnitude of benefit) for every 10% increase in control patients receiving subsequent therapy.

Even though we pooled PFS and OS in this analysis, “pooling was justified because the core question concerns trial validity under inert controls, hazard ratios guide regulatory approval, and both OS and PFS distortions may arise from the same issue—depriving control patients of active therapy.”

A simple rule to assess the control arm - “Would you randomize your own mother?”

In our discussion, we acknowledge that “some level of post-protocol care in control-arm patients is inevitable”. Also, if a framework is provided by the Helsinki Declaration, this means the use of placebo, in some cases, can be justified.

However, in our work, the minimum rate of subsequent systemic therapy was 22 %, really broadly questioning the use of placebo and inert controls in those settings.

Whenever you consider a control arm, ask yourself: would I be comfortable assigning patients to it? “Would you randomize your own mother?” (from Vinay Prasad). If the answer is no, it’s a strong signal to investigate rigorously whether the control is outdated, distorted, or unfair.

Check out the full paper for more insights, and thanks to my co-authors Christopher Rios Alyson Haslam