The puzzle of PARP inhibitors plus ARPI in Prostate Cancer: 12 mutations, 3 trials, and 5 different labels.

In a new paper just published in eClinicalMedicine, part of the Lancet group, we discuss, together with Sahar van Waalwijk, the fascinating consequences of three trials that all studied PARP (Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase)-inhibitors (PARPi) in combination with androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPI) for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

PARP-inhibitors mechanism of action

PARP is a protein involved in repairing the DNA when wrong copies are made, which tipically occurs in cancers.

PARP inhibitors are drugs that are most effective when other DNA repairing genes are already impaired in cancer. These genes are called homologous recombination repair genes (HRR), which can lead to homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD). Those are usually grouped in two buckets:

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations (BRCAm, “m” stands for mutation) makes one group.

and non-BRCA mutations (non-BRCA HHRm) constitute the other group, with mutations individually less frequent: ATM, ATR, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANC, MRE11A, PALB2, RAD51C and others.

Three trials combining PARPi and ARPI

The three trials are PROpel, TALAPRO-2 and MAGNITUDE. They resulted in five different labels showing inconsistencies between the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). In our paper, we highlight issues which are mainly:

The flaws in the trial designs of mainly PROpel and TALAPRO-2

The lack of harmonization of HRD

Uncertain benefits of combination therapies and control arm issues

The differences in approvals and labels between the FDA and the EMA

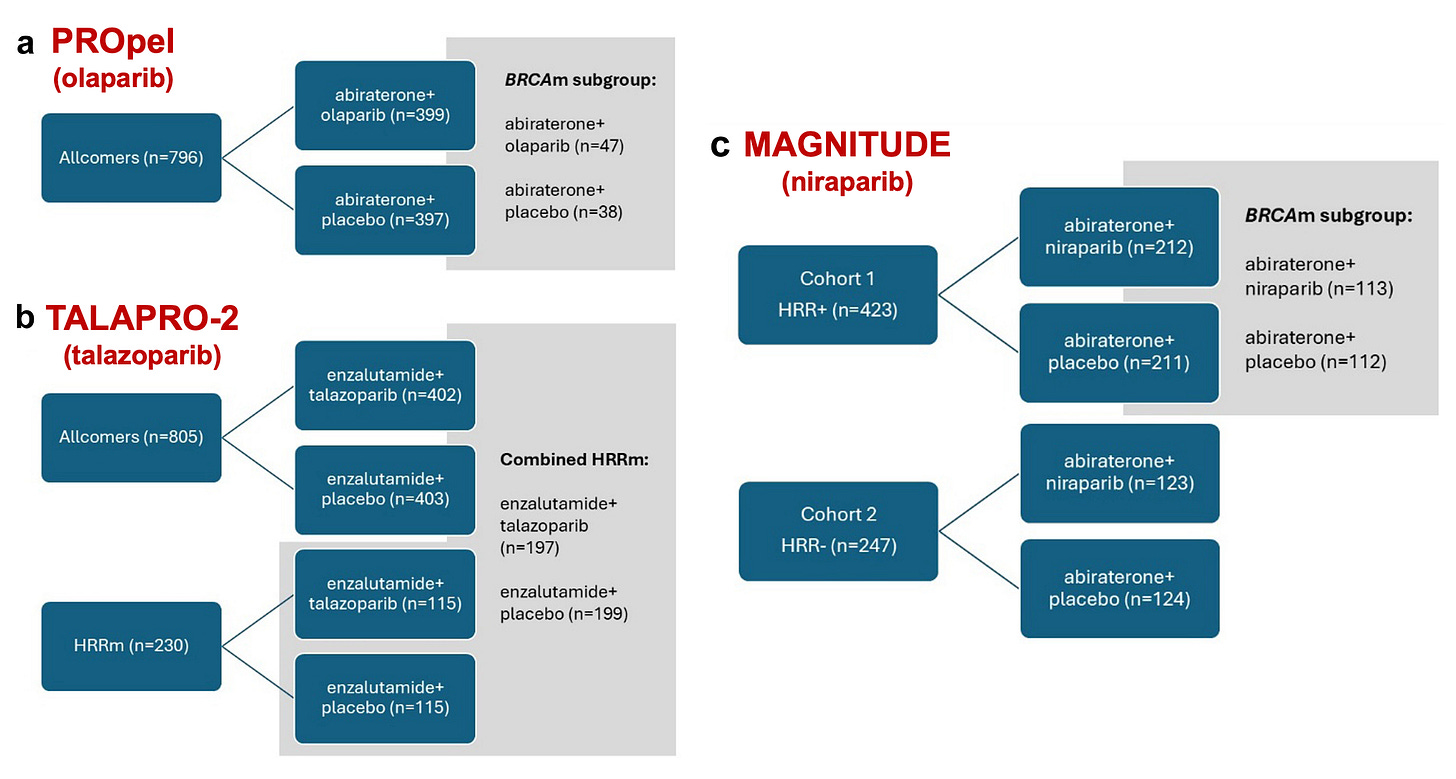

Trial designs

In PROpel, 796 mCRPC patients were randomly assigned to olaparib or placebo with abiraterone (plus prednisone or prednisolone). The trial adopted an all-comer design with no stratification or prespecified alpha-controlled analysis for BRCAm/HRRm, despite the EMA’s recommendation to do so.

the primary endpoint radiologic progression-free survival (rPFS) was met.

no statistically significant difference in overall survival (OS) between the two groups was observed.

both regulatory agencies suspected that the potential benefit might have been driven by the subgroup of patients with BRCAm (n = 85), in which both rPFS (HR 0.24) and OS (HR 0.30) were significantly improved.

in contrast, in the non-BRCAm group (n=427), both endpoints were not met.

In TALAPRO-2, 805 mCRPC patients were randomly assigned to talazoparib or placebo with enzalutamide. This trial also adopted an all-comer design, albeit with a stratification for HRR mutation. A second cohort of HRRm patients only followed, and the combined HRRm population across both cohorts was analysed.

both independent primary end points of rPFS in the all-comers cohort and in the combined HRRm population were met.

rPFS and OS for non-BRCA HRRm were not significant.

final OS analysis was significant in the overall population. However, better in HRRm subgroup (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.36–0.83; p = 0.0035) but not significantly different in non-HRRm or unknown patients.

In MAGNITUDE, there were two cohorts: 423 HRRm mCRPC patients in cohort 1 and 247 non-HRMm CRPC patients in cohort 2. They were randomized to either niraparib or placebo combined with abiraterone (plus prednisone or prednisolone). Cohort 2 was stopped early because of futility in a pre-specified interim analysis. As the greatest effect was expected in BRCAm, a protocol amendment was implemented in 2020, approximately one year after the start of the trial, to modify the statistical analysis plan. The BRCAm subgroup was assigned as the primary efficacy population to be analyzed first. If statistical significance was reached in this subgroup, the entire Cohort 1 population would then be tested.

rPFS in the BRCAm subgroup was met

rPFS in the overall Cohort 1 was also met

no significant effect was seen in non-BRCA HRRm patients and even a potential detrimental effect on overall survival (OS HR 1.13, 95% CI 0.77–1.64).

Lack of harmonization of HRD

The definition of HRD is not consistent across trials. For example, the PROpel trial did not consider ATR, NBN, FANCA and MRE11A genes 4 whereas TALAPRO-2 included MLH1, a mismatch repair gene, which is not part of the HRR pathway.

Ideally, researchers should be given access to both biomarkers and clinical data. Aggregating data can increase statistical power and help us better understand how different HRRm impact treatment outcomes.

Uncertain benefits of combination therapies - and suboptimal control arm

In contrast to monotherapy, where ineffective drugs are discontinued, PARP inhibitor use can continue even if the effectiveness is driven only by ARPIs. This potential over-treatment comes with increased toxicity and higher healthcare costs.

Also, in these studies, patients in the control arm who had previously received an ARPI arguably received substandard care by being assigned another ARPI (the so-called “ARPI-switch”). The EMA also raised concerns about patients with visceral disease who had not received docetaxel but had been treated with an ARPI, and therefore restricted the indication to those for whom chemotherapy is not clinically indicated.

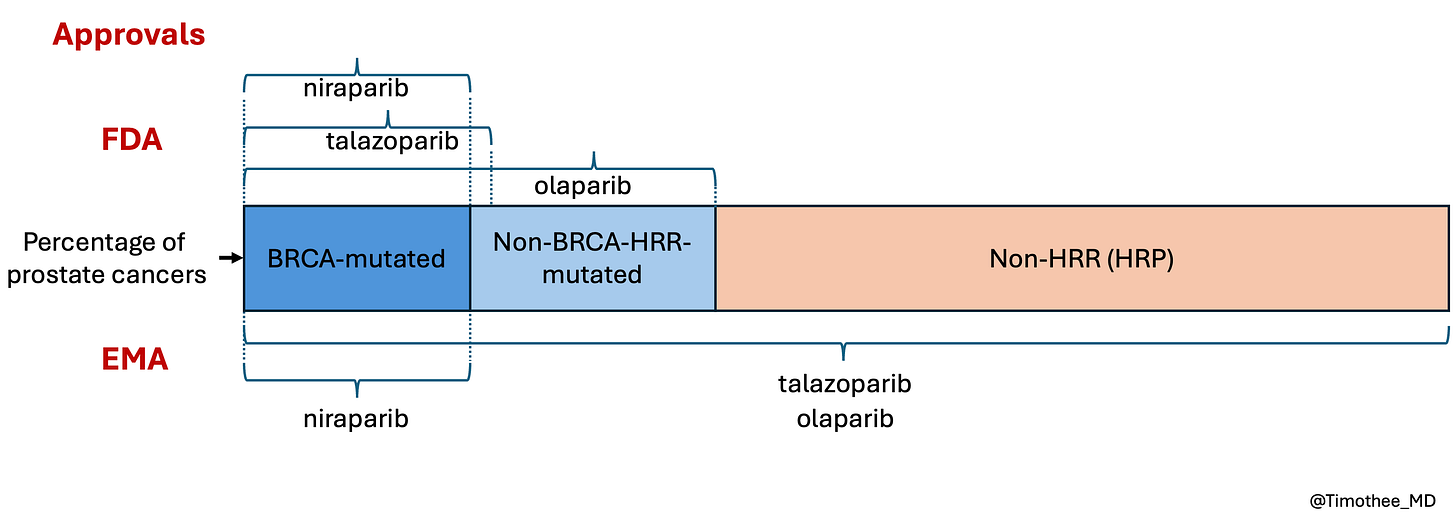

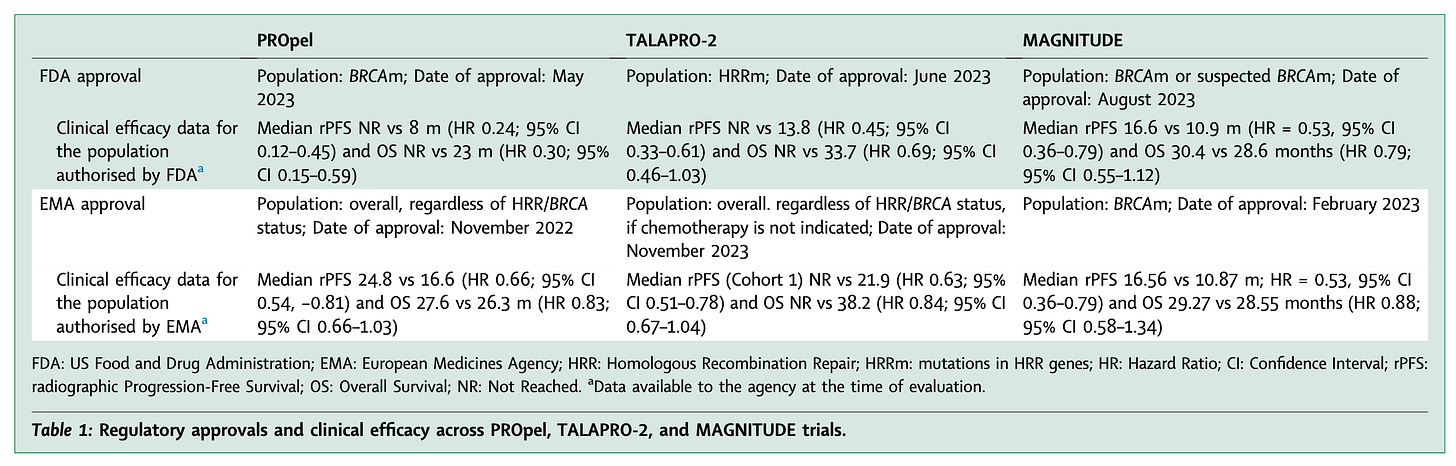

Differences in labels between regulatory agencies

Of the three trials, only MAGNITUDE (niraparib) led to the same conclusion from both the EMA and FDA, as its design effectively identified the benefiting subgroup. The discrepancies observed in the assessment of the other two trials stem from differences in their design.

In general, if a positive trial demonstrates benefit in a biomarker-positive subgroup, FDA guidance allows approval only for that population. In contrast, in the case of both PROpel and TALAPRO-2, EMA authorized a broad label for the overall population. (see Table 1 below)

In other words, the FDA was more restrictive, with a biomarker-driven approach, than the EMA when considering labels (see also unpublished figure below).

There is a sad paradox. MAGNITUDE had a better design and informs treatment decisions better than the other trials, leading to a more restricted label, consistent in both US and Europe. In contrast, the two other companies seem to be rewarded wtih broader labels despite the design flaws and despite ignoring recommendations by the agencies.

Conclusion

Our work highlights how inconsiscies in trial designs may lead to different conclusions. An optimal trial would prospectively determine HRR status using a standardized definition, followed by stratified randomization into biomarker-defined cohorts (e.g., BRCA1/2, non-BRCA HRRm, and non-HRRm). Each cohort would be independently powered to enable definitive conclusions, and to avoid the risk of one cohort driving the benefit of a wider cohort (“adjacent subgroups” design instead of “nested subgroups” design). The control arm should reflect contemporary standard of care, allowing a fair comparison between combination therapy vs optimized sequential use.

Even though no trial is perfect, these funding principles would limit the risk that a trial is ultimately non-informative stemming from its very inception.

See our full paper openly available here.

The repeated design of clinical trials with suboptimal control arms is concerning and may exaggerate the effect of the drug(s) under study.

Good work, thank you. In the real world, do PARPs have any real benefit? (not being skeptical, just I don't hear good things in just about any indication)