The PATINA trial – palbociclib maintenance in metastatic breast cancer.

What is the best 1st-line strategy in patients with HR+/HER2+ advanced/metastatic breast cancer?

PATINA was a phase 3 open-label trial testing maintenance palbociclib, in patients with HR+/HER2+ metastatic breast cancer who did not have disease progression after 4 to 8 cycles of first-line chemotherapy plus HER2-targeted treatment.

In addition to receiving maintenance HER2 and endocrine therapies, 518 patients were randomly assigned to receive palbociclib – an anti-CDK4/6 inhibitor – or no other therapy. The primary end point was investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS).

The study was just published in the New England Journal of Medicine and there are several points to raised while looking at this study report.

Does the reported PFS gain seem reliable?

In PATINA, the authors report a 15 months median PFS gain, with 44.3 months median PFS in the palbociclib group and a 29.1 months median PFS in the control group (HR = 0.75; 95%CI = 0.59 - 0.96; two-sided P=0.02).

Two key elements have to be noted, that could have amplified the gain as reported.

1- Informative censoring.

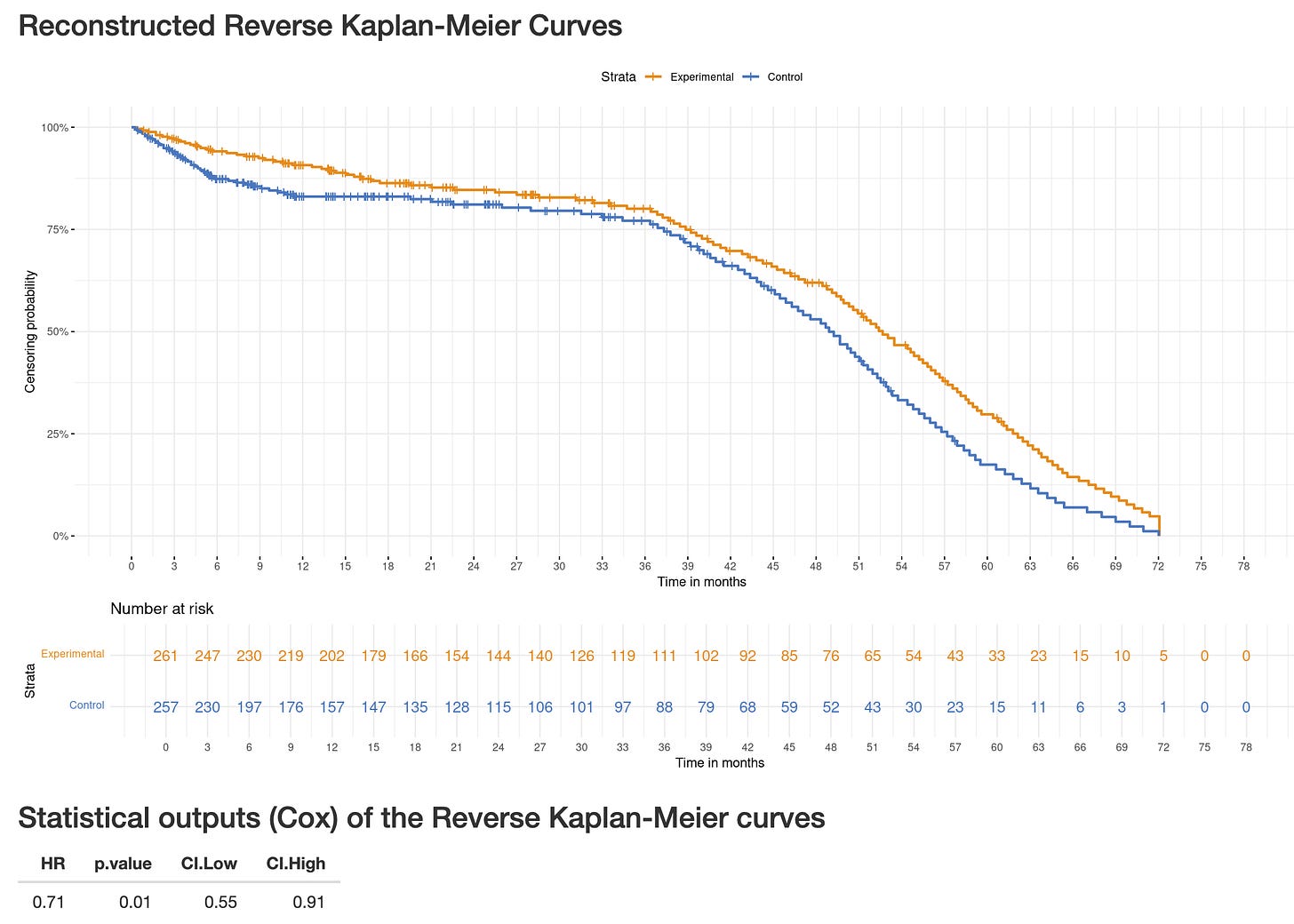

The numbers of censoring patients are (sadly) unreported in the NEJM publication, however, one can estimate those by using digitized curves. In the BREAKING-ICE App, select PATINA-PFS and you see a significant early imbalance in censoring with 5.3% of patients censored over the first 6 months in the palbociclib group and 12.1% of them in the control group.

Why patients left in excess after being assigned the control group?

Some may have been disappointed by allocation to the control arm. Some may have been eligible for other trials and left PATINA, possibly encouraged by trialists.

Now here is the crux of the issue: are patients lefting PATINA in excess the same as those remaining in the control group? A reasonable assumption in that those patients may have been more connected, had more options, and may have been lower-risk patients in terms of presenting an event. If so, the remaining control patients would be enriched for higher-risk patients, potentially inflating the observed PFS difference.

The Reverse Kaplan-Meier analysis explore whether informative censoring could have occured, by flipping events and censoring events. In PATINA, both this plot and its corresponding “Cox” analysis, being “statistically significant”, show informative censoring could have occured. (Go to the Reverse-KM App© and select PATINA-PFS, see screenshot below).

2- Open-label design and investigator assessment.

We know some subjectivity can affect investigators when “calling” a progression event based on a CT scan: that’s why many trials use blinded-independent central review (BICR).

Here, the combination of an open-label trial with no BICR could have also amplify the PFS gain.

“Early progression calls” in the control arm. In an open-label setting, investigators may be more inclined to declare progression earlier in control patients when scans are borderline or tumor growth is still below formal RECIST thresholds, because there’s a practical incentive to move quickly to the next line of therapy or another trial.

“Late progression calls” in the experimental arm. If clinicians believe the new therapy is helping, they may be less likely to call a progression on equivocal imaging, thereby delaying the recorded progression date.

Symptoms deterioration interpretation differing by arm. The decision to prescribe non-scheduled CAT-scan is often influenced by symptoms and clinical course. Control patients with worsening symptoms may trigger a CAT-scan sooner than a patient in the experimental arm, with the same symptoms being attributed to toxicity. In the last situation, the official progression is delayed to the next scheduled CAT-scan.

In conclusion, given the possible biases introduced by informative censoring, an open-label design, and the lack of BICR, the PFS gain as reported may have been artifically inflated.

Is PFS a direct clinical endpoint?

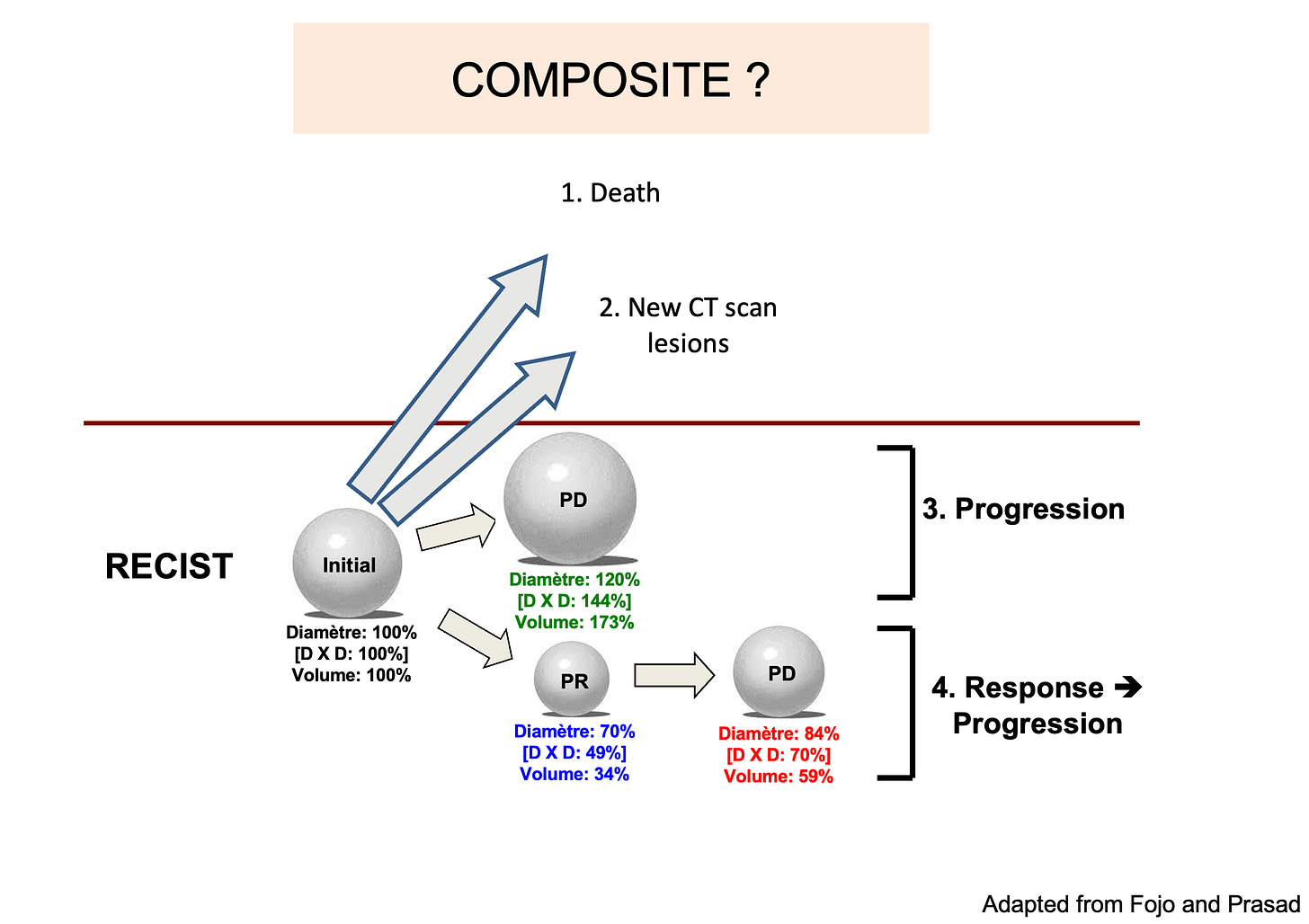

The answer is no. PFS is a composite time-to-endpoint enpoint: progression (largely based on CAT-scan thresholds) or death can both count as an event. (see the figure below).

One issue is that often, and this is the case in PATINA, we don’t have the“breakdown” of PFS events. In other words, we don’t know whether the event was a CAT-scan progression, or death (see this work in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, by Anushka Walia and Vinay Prasad, with a key figure below).

Without kwowing the breakdown of events, the relevance of a PFS gain is difficult to assess, as death and an asymptomatic progression are very different events, still counting similarly in PFS estimates.

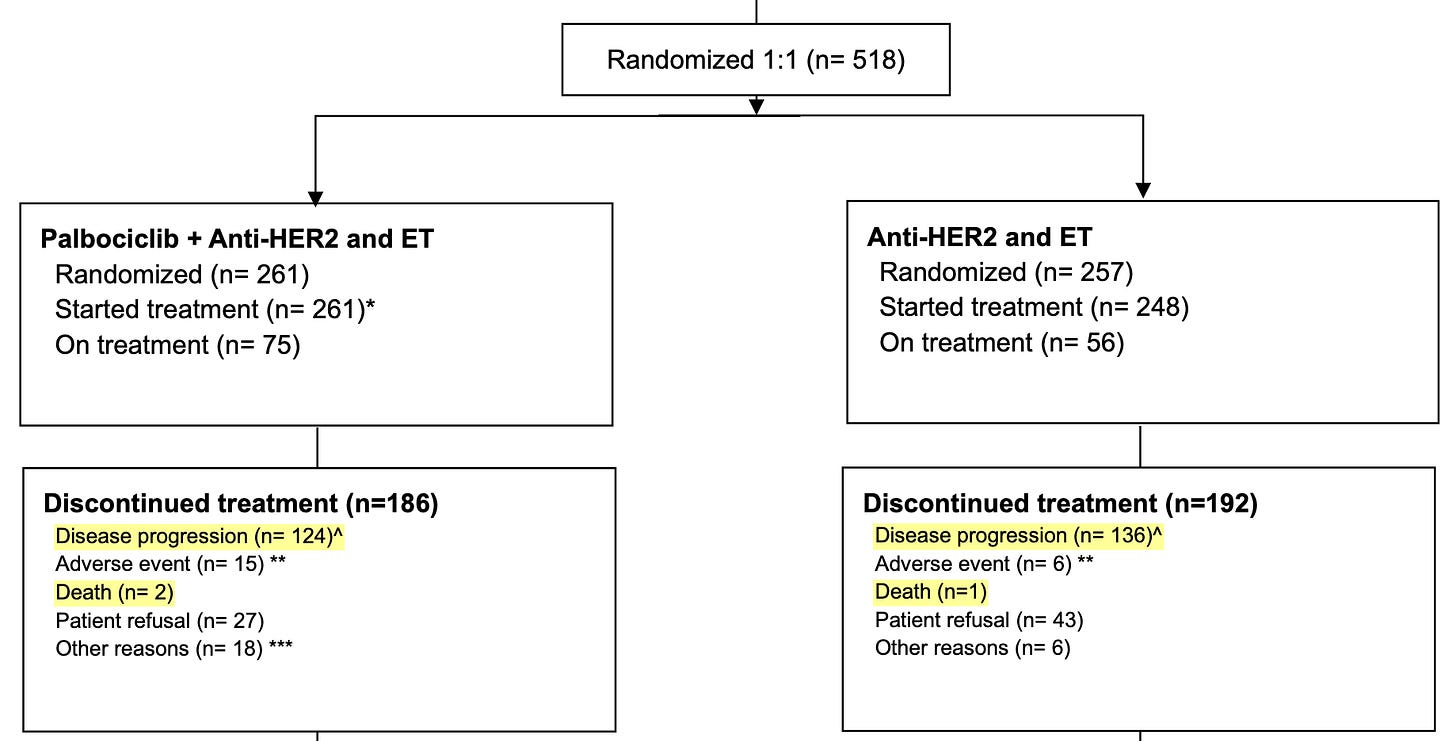

In PATINA, we have only an indirect clue that most events were disease progressions and not deaths in the Figure S1. CONSORT Diagram, as the reason for discontinuation of treatment was death in only a few instances (2 patients in the palbociclib group, and 1 patient in the control group)

Is a PFS gain clinically meaningful?

This question is slightly different from the definition of PFS: even though PFS is not a direct clinical endpoint, we often based our treatment decisions based on progression. As a results, and even if the progression is totally asymptomatic, the event will have a clinical impact on patients simply by triggering a change in care.

“A surrogate endpoint is an endpoint that patients didn’t know mattered until a doctor told them it did” (from Adam Cifu, MD)

Some may find this quote provocative, but it highlights that the relevant question about any surrogate, and this applies to PFS, is whether the gain will ultimately led to better outcomes for patients, which are generally accepted as either living longer (Overall Survival gain), living better (Quality of life - QoL - gain), or both.

In PATINA, some have argued a median PFS gain of 15 months (29 to 44 months) is undoubtely clinically meaningful, as this delay the time to the next line of therapy, which is often chemotherapy. This argumentation is assuming that those patients have a QoL gain by delaying the progression event.

This misses 1) the QoL data from PATINA are not yet published, and the data presented so far show HRQoL was “maintained” 2) patient are receiving an additionnal therapy – palbociclib – which does not really fit into the category of a “well-tolerated drug”.

Is palbociclib in PATINA “well tolerated”?

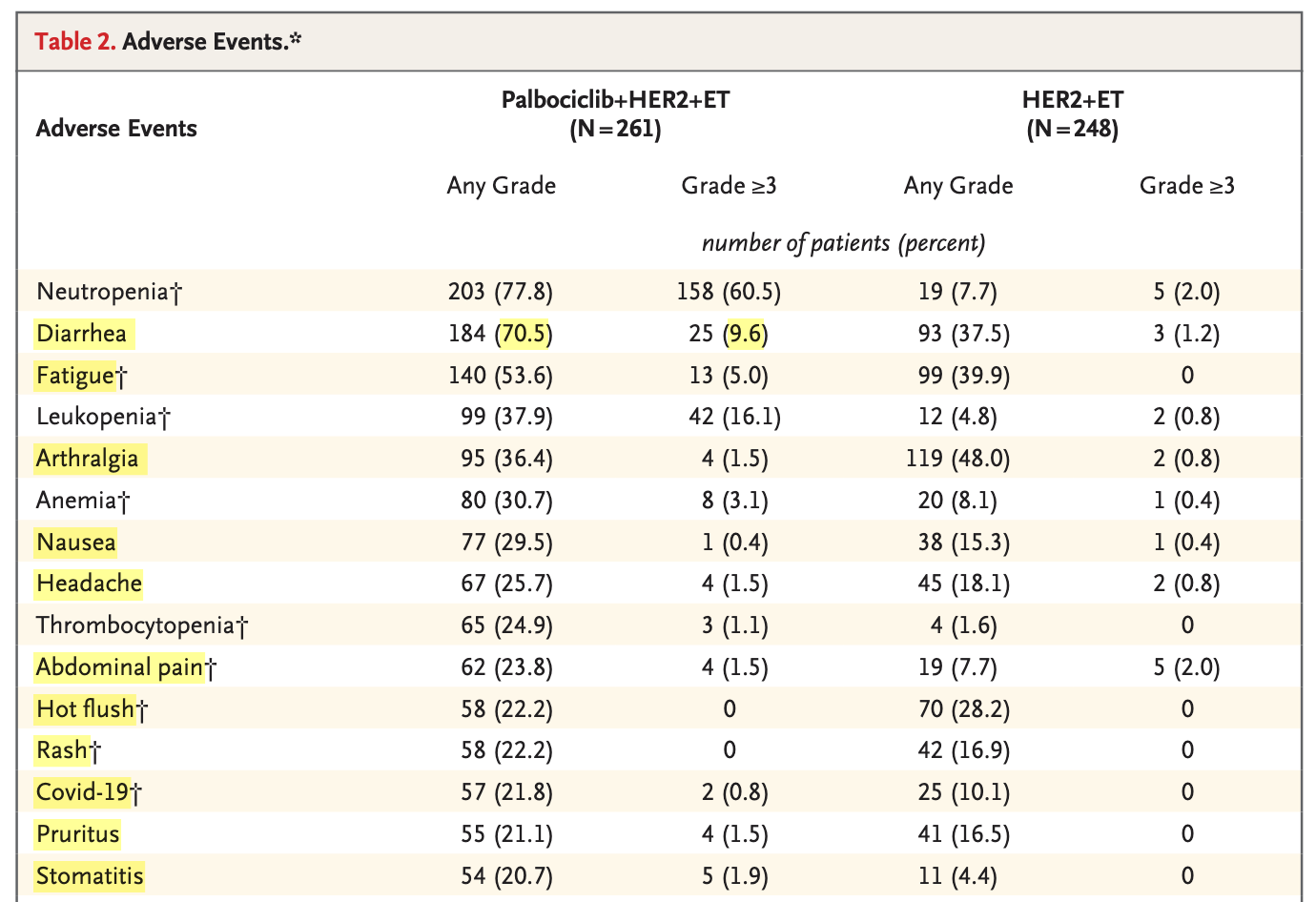

As seen in the supplementary (Table S5 below), 55% of patients receiving palbociclib in PATINA had at least one dose interruption; 28% had 1 dose reduction and another 30% had 2 dose reductions.

In Table S7, we can see that 18.1% of patients experienced adverse events “at least possibly related to treatment that led to palbobiblic discontinuation”.

Not all adverse events affect patients equally: some are asymptomatic lab abnormalities, while others are clinically meaningful symptoms. In PATINA, among the 15 most frequently reported adverse events in the palbociclib group, 11 of 15 (below in yellow, excerpt from Table 2) are primarily clinical rather than laboratory abnormalities.

Conclusions — context with DESTINY-Breast09 and HER2CLIMB-05

The main efficacy results from PATINA – the PFS benefit – may have been amplified by informative censoring and the unblinded nature of both treatment allocation and progression assessment.

We lack the breakdown of PFS events which could inform treatment-decision making with patients : there is a huge difference between a CAT-scan progression and death.

While the QoL data conclude that HRQoL was maintained (presented, not published), many limitations can affect QoL analyses in general, and QoL data should not obfuscate the obvious: the added toxicity of taking an additionnal compound.

The timing of the PATINA publication is surprising, occuring more than one year after the results were presented in December 2024 in San Antonio. Recent publications of novel strategies in first-line or maintenance treatment of patients with HER2+ advanced or metastatic breast cancer may be one possible explanation.

DESTINY-Breast09 studied first-line HER2+ advanced/metastatic breast cancer (54% of patients were HR+) and showed that trastuzumab deruxtecan plus pertuzumab significantly improved BICR-assessed PFS versus taxane–trastuzumab–pertuzumab (THP) (median 40.7 vs 26.9 months; HR = 0.56) with high response rates but a higher risk of adjudicated interstitial lung disease (ILD) or pneumonitis (12.1%, including rare grade 5 events).

HER2CLIMB-05 studied first-line maintenance in HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (53% of patients were HR+) after induction therapy and showed that adding tucatinib to trastuzumab/pertuzumab significantly improved investigator-assessed PFS versus placebo (median 24.9 vs 16.3 months; HR = 0.64), with diarrhea and transaminase elevations common and 13.5% discontinuing tucatinib due to treatment emergent adverse events.

Brilliant analysis... I’ve just read the paper, and one thing is rather puzzeling. They write: “The trial was powered [ ] on the assumption of a median progression‑free survival of 13.0 months in the standard‑therapy group and 19.5 months in the palbociclib group.” This assumption is somewhat surprising, because these medians are very close to those reported years ago in CLEOPATRA (PFS 12.4 m with placebo vs 18.7 m with pertuzumab). In other words, their expected PFS for both arms is much shorter than what one would expect.... This is while PATINA recruited "induction-responder population" (so more favourable biology), with almost twice as many HR+ patients as in CLEOPATRA... all these should increase PFS rather than shorten it... So why do they predict such low PFS in their hypothesis?

Thank you for this thoughtful and carefully argued appraisal of the PATINA trial. The discussion on informative censoring is particularly important, as this issue often receives less attention than it deserves in oncology trials.

While the trial provides valuable clinical insights, analyses like yours remind us that methodological nuances can meaningfully influence interpretation. Constructive scrutiny of these aspects is essential if we aim to strengthen the design and credibility of future studies.

At the same time, it is important to recognize that this remains a hypothesis-generating perspective, and alternative interpretations may reasonably emerge as the data are further examined and debated.

Thank you again for offering such a stimulating and intellectually honest perspective. I look forward to your continued exploration of these methodological issues, as this kind of critical reflection is invaluable to the oncology community.