When the Follow-Up Ends Too Soon: Rethinking Long-Term Benefit of Immunotherapy

Over the years, our research group has written a lot on immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in cancer, in part because of the excitement over durable responses in certain tumor types.

A key question, however, is how many patients derive long term benefit? Much of the research around ICIs has had short follow-up, and while results are impressive for some tumor types, long-term data are not always reported.

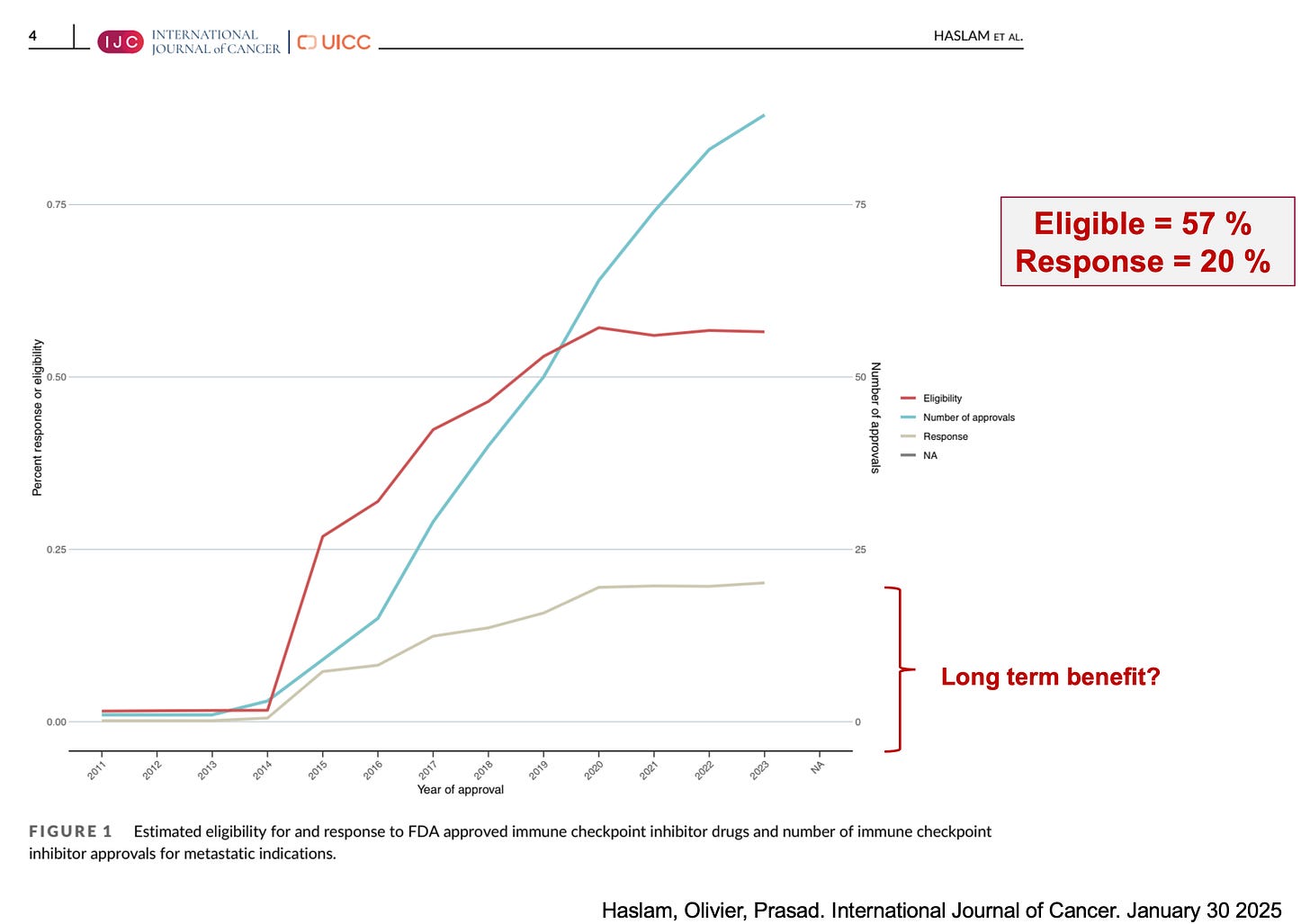

Indeed, the number of approvals for this drug class has increased, and the percentages of individuals who are eligible for and respond to these drugs have also increased (full access here, and a key figure below).

Several frameworks, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Value Framework Tail of the Curve and the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO MCBS) have been developed to capture long-term benefit. However, there are discrepancies between the frameworks, and they both have limitations. As such, conclusions about long-term data from these frameworks may be limited.

Our new work - assessing long-term survival data

To better assess long-term benefit, we reviewed all FDA-approved oncology ICIs in the metastatic setting (2011-2023) (full access here). Using trial information, we searched for the most recent publication reporting overall survival (OS) for each ICI.

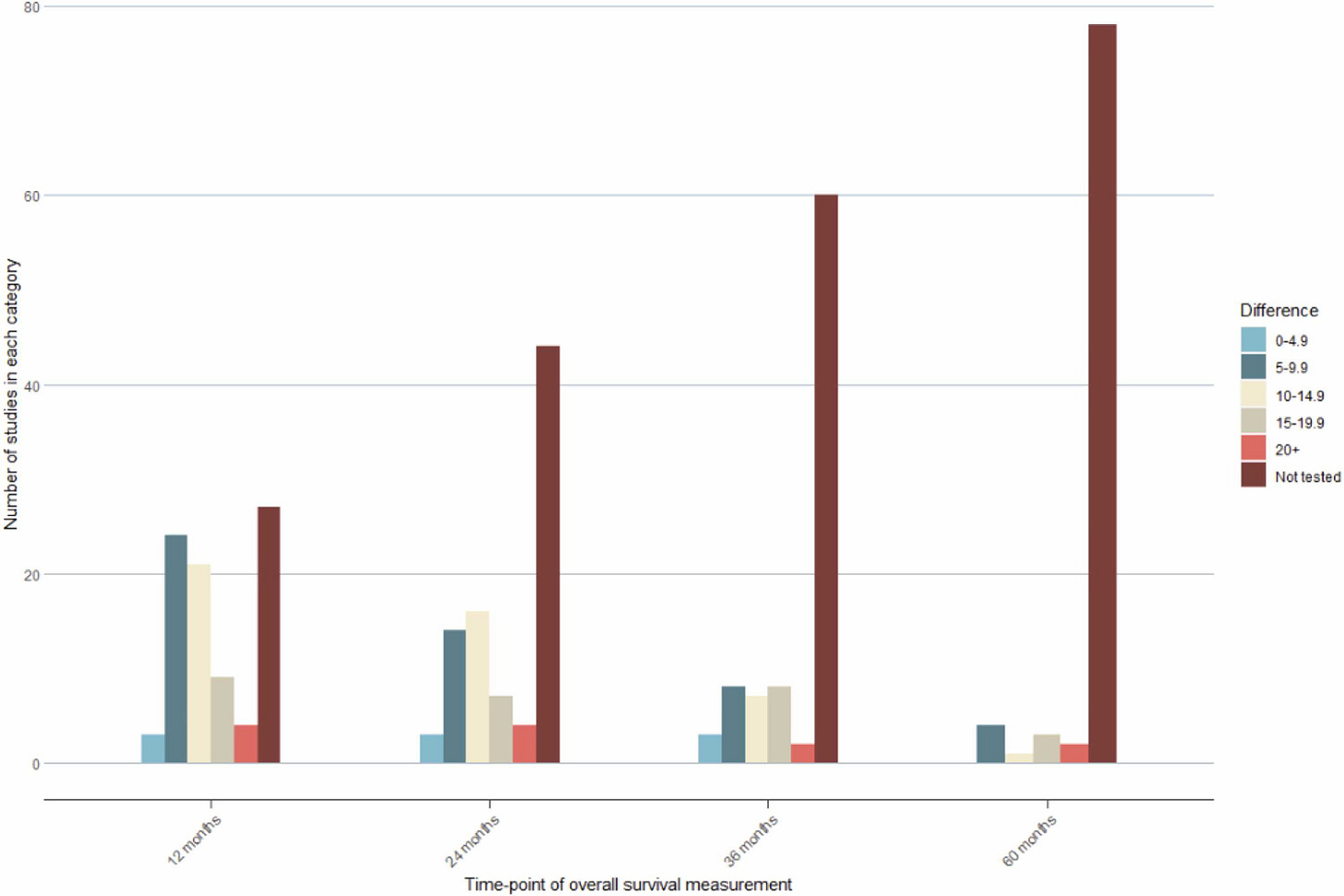

The median duration of follow-up for all drugs was 26 months. Of the 88 drugs evaluated, 20 (23%) qualified for ASCO’s tail of the curve bonus and 27 (31%) did not report median OS. Moreover, 50% of studies did not report OS at 24 months, 68% did not report OS at 36 months, and 89% did not report OS at 60 months. Just under one-third of trials report OS data for patients as long as three years, and just over 10% report OS data at five years. Ideally, we would have a better idea of long-term benefit for all drugs and not just a minority of them.

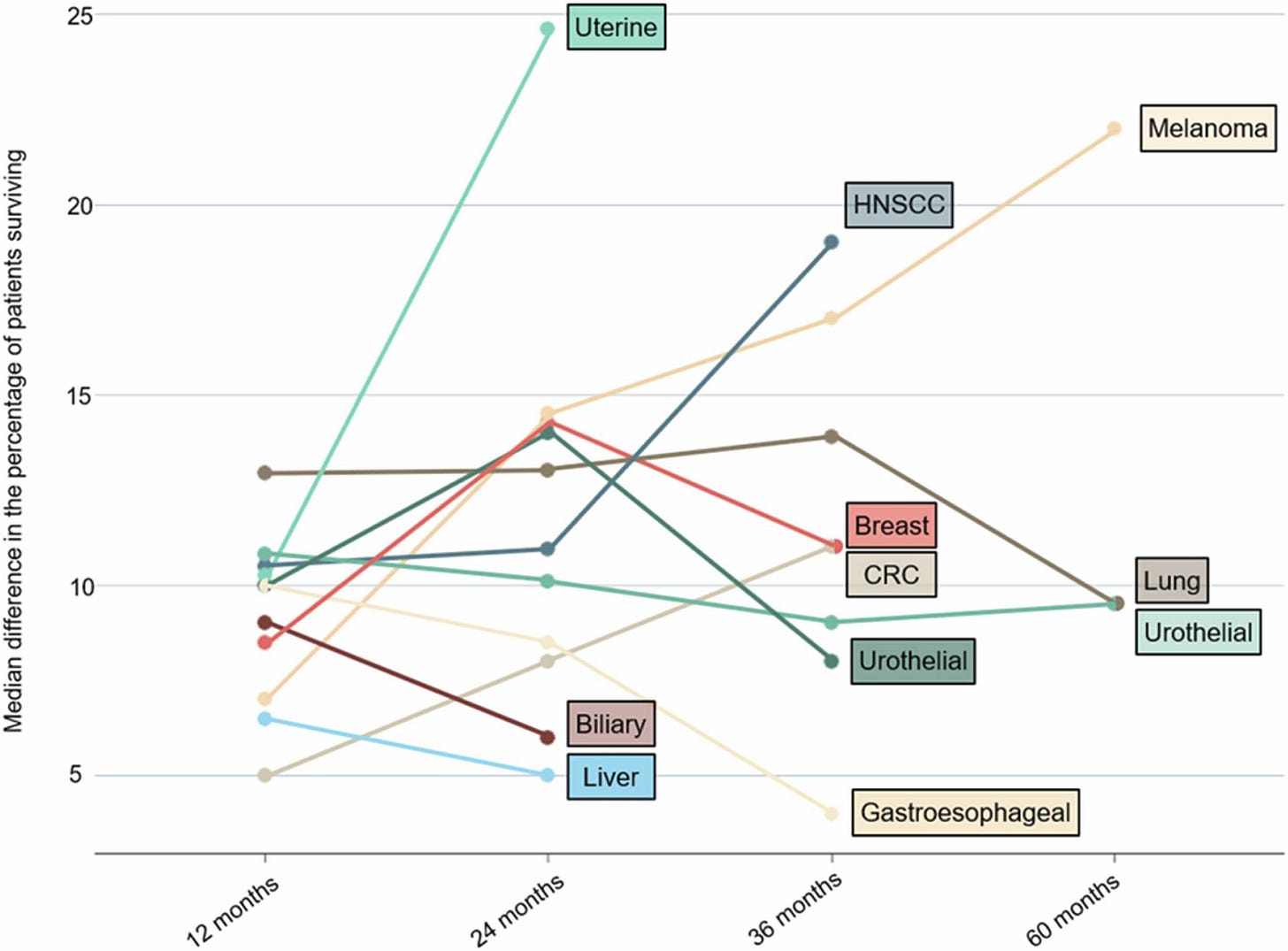

One take-away from the study is that long-term OS and benefit is limited to a few tumor types, such as melanoma. Hepatobiliary and cervical tumors not only have short follow-up, but they often have small differences in the percentage of patients surviving between the intervention and control arms. Long-term benefit may be the exception rather than the rule when it comes to ICI therapies.

Another take-away is that long-term response appears to be at least partially related to tumor biology, not just the difference in OS provided by the ICI. This was demonstrated by the lack of correlation between the longest time with at least 10% of patients at risk and the absolute difference in survival.

It is important to consider that these numbers reflect clinical trial experience, so real-world benefit may be even less since clinical trials often include younger and healthier patients than patients in the real-world.

In summary, the gathering and reporting of long-term survival data on ICIs should be incentivized to provide information to providers who can assess the value of these drugs for their patients.

Great points

The disconect between trial excitement and actual long-term data is such an important point. I hadn't realized so many approvals had follow-up under 3 years, that's concerning when we're making major treatment decisoins. The finding that long-term response relates to tumor biology rather than just the ICI itself is fascinating. Does this suggest we should be more cautious about extrapolating results from melanoma studies to other tumor types? The real-world vs clinical trial patient difference you mention makes this even more critical for practicing oncologists to understand.