How To Study Drugs With Apparent Massive Effect Sizes, Still Using Randomization?

We proposed a trial design to answer this question.

The parachute analogy is often used in medicine to argue that studying certain interventions is unethical, comparing them to parachutes, with exceptionnally large effects. However, most medical interventions are far from being parachutes. (more on this here and here).

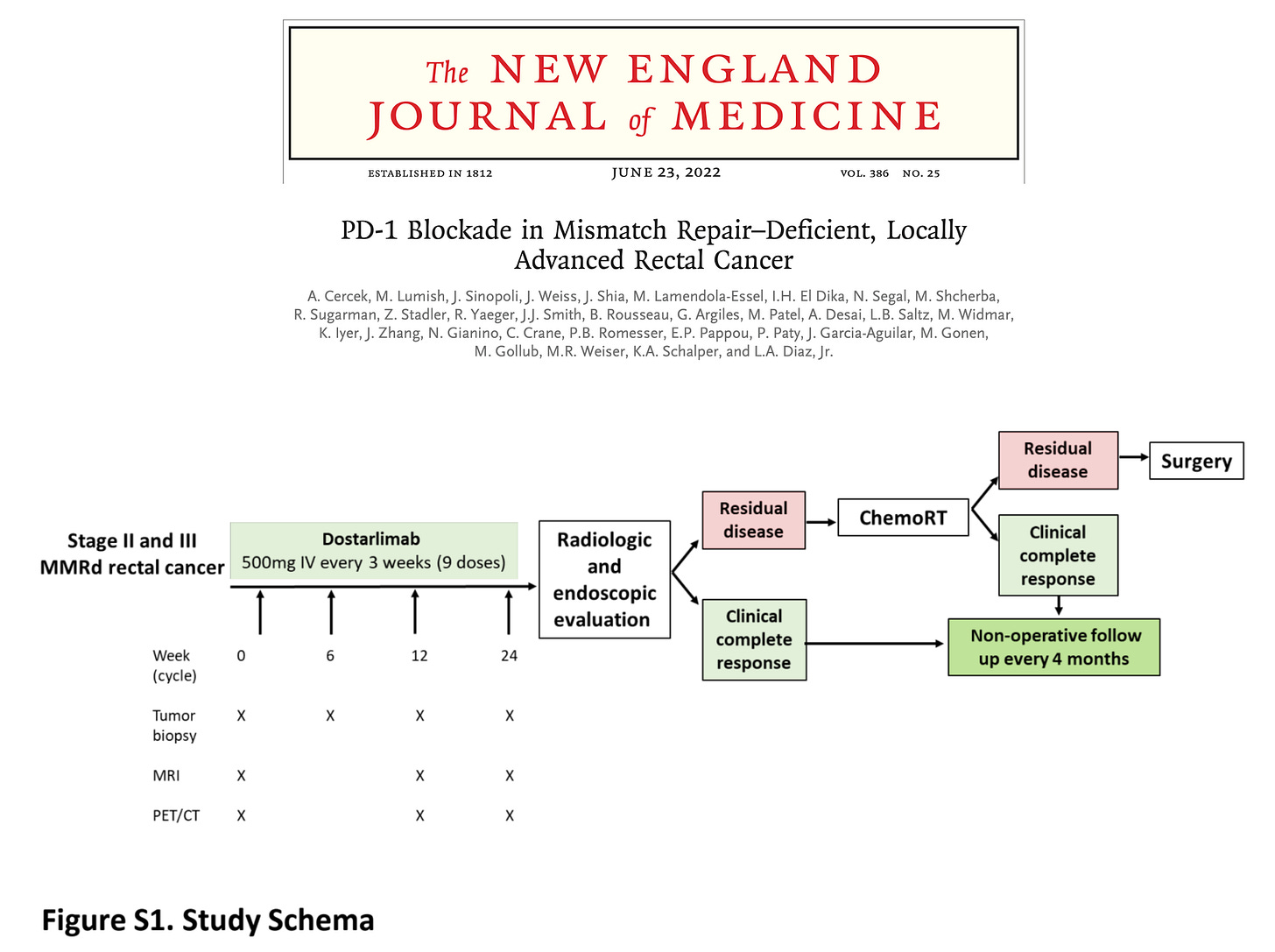

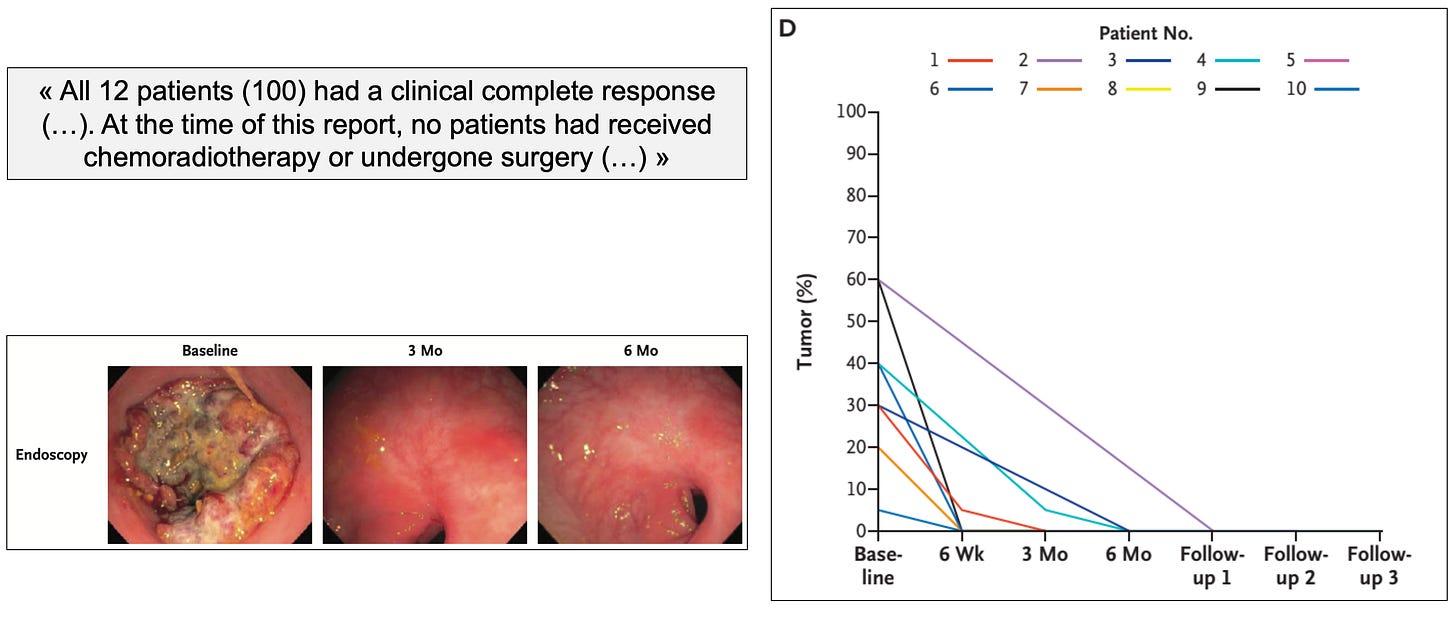

Still, in few instances, interventions appear to have exceptional effect size. In those cases, with Logan Powell and Vinay Prasad, we proposed a novel trial design that both maintain a randomization component while being acceptable and ethical for patients. We published this proposal in Trials after a study showed impressive results with dostarlimab – an anti-PD1 therapy – in patients with MSI-high rectal cancer.

How to study the few potential “parachutes” in medicine?

The abstract of our work sets the stage:

“Dostarlimab (Jemperli, GlaxoSmithKline) is an anti-programmed death receptor-1 monoclonal antibody (anti-PD-1) recently tested in a non-randomized, phase II trial (NCT04165772) which included patients with mismatch repair-deficient, locally advanced rectal cancer. Among the first 12 patients treated with dostarlimab, 100% achieved a clinical complete response with no patients experiencing progression or recurrence to date. Most impressive, none required chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery the prevailing standard of care. In this paper, we discuss the impressive results of this trial and how they relate to cancer policy, as well as propose a novel trial methodology to assess dostarlimab.”

The study was presented during ASCO 2022 and published the same day in the New England Journal of Medicine. Below are the study schema and key results:

To gain knowledge, incorporate randomization whenever possible

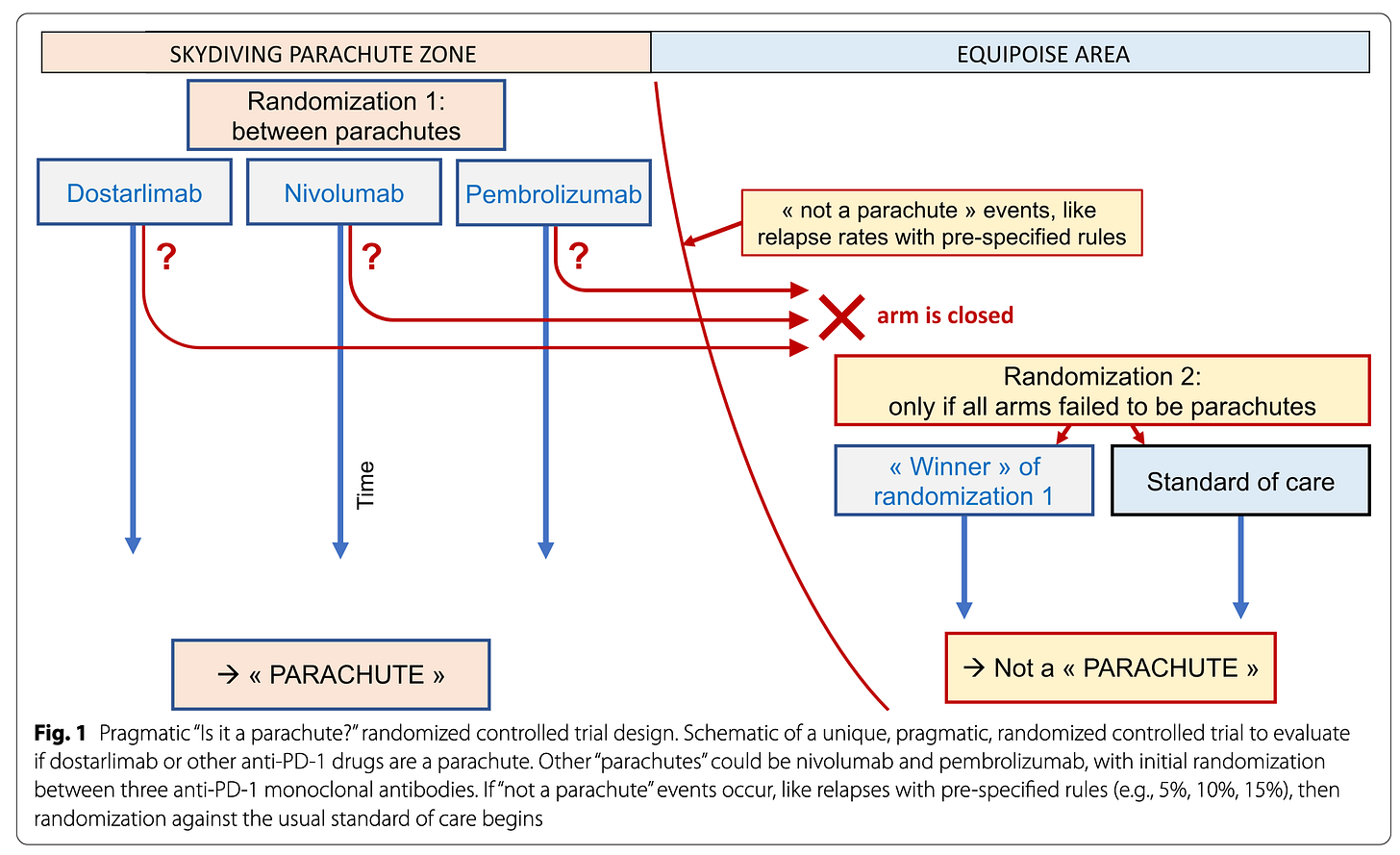

A class-effect? In the case of dostarlimab, everyone wondered if such impressive results were due to the drug itself or whether similar results could have been achieved with any other anti-PD1 therapy. Randomization may answer this very question.

Parachutes themselves have evolved over time, and paragliding today is not exactly similar to jumping with parachutes 50 years ago in terms of physical trauma and risks taken.

One can pre-specify rules – like a number of events – defining the “Skydiving parachute zone” (on the left). In this zone, you don’t want to randomize patients to “no parachute”, however you can use randomization to clarify, for instance, if there is a class-effect or not. Randomization between different “parachutes” – different anti-PD1 molecules – is both reasonable and informative.

If the “Skydiving parachute zone” rules are crossed, then the trial will move to a more conventional “Equipoise area” (on the right) where randomization versus the usual standard of care is again justifiable and acceptable. We illustrated this in the key figure below.

Concluding words

Although randomization is not always appropriate or feasible in medicine, the question of incorporating some degree of randomization into trial design should always be considered. Randomization is a powerful tool for generating knowledge and should not be dismissed, even for interventions or compounds with seemingly very large effect sizes. (our full work is accessible here).

love these thought provoking articles... I save every one and flip through them occasionally to think about them and formulate ideas/questions whenever I see a trial

Thank you for a very interesting article (and proposal).

Of course, this highlights a more general observation which is that “adaptive” trial designs (by which I mean those in which randomization algorithms are tweaked continuously according to results accruing in real-time) are, in general, underutilized.

The main roadblocks to their use, lack of reliable communications and centralized computerized management systems, no longer exist.

Yet such designs can potentially shorten trials significantly and / or reduce the numbers required, and / or make some otherwise difficult trials (because of recruitment) easier to perform.