Let's get ready for ESMO 2025 with the KEYNOTE-905 trial! Does EV-Pembro in perioperative bladder cancer set a new standard of care?

We should wait to see the data at ESMO before making any decisions.

At a medical conference – especially at the largest ones – it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the amount of data being presented. One of the best ways to avoid this is to come prepared: know what you want to focus on, what questions you have, and what concerns you might anticipate.

Survival benefit announced by press release.

There’s a lot of excitement around the KEYNOTE-905 trial after the results announced via press release showed that enfortumab vedotin (EV) plus pembrolizumab (pembro) improved survival “for Certain Patients with Bladder Cancer When Given Before and After Surgery”.

The trial evaluated an association of enfortumab vedotin (EV), a Nectin-4 directed antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), plus pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, as neoadjuvant (3 cycles) and adjuvant (6 combination cycles followed by 8 additionnal pembrolizumab cycles), as compared to surgery alone, in patients with localised muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are “not eligible for or declined cisplatin-based chemotherapy”.

The results will be presented for the first time during one of the Presidential Sessions at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual conference, to be held in Berlin this October (program here).

The slide below summarizes the study design and outlines the key concerns/questions I anticipate.

1) EV-pembro is toxic

The study enrolled patients considered frail – either ineligible for or declinin cisplatin-based chemotherapy – with the aim of offering a less toxic regimen: EV–pembro before and after surgery.

However, EV–pembrolizumab is a regimen with toxicities that are not so far, in terms of side effect frequency, to platinum-based chemotherapy. In the EV-302 trial, EV–pembrolizumab was compared with platinum-based chemotherapy in the first-line setting of advanced bladder cancer, with more than half of control group patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy and the remainder receiving carboplatin-based chemotherapy. In EV-302, treatment-related adverse events of grade ≥3 occurred in 55.9% of patients receiving EV–pembrolizumab and in 69.5% of those in the chemotherapy group.

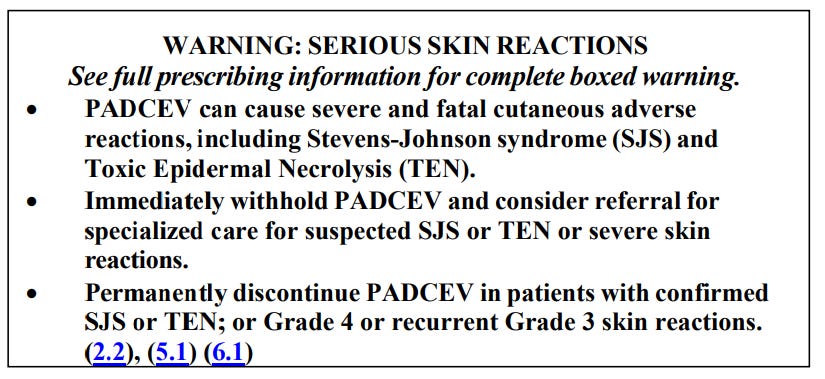

Enfortumab vedotin can be very toxic, as you can see in the warning box in the FDA labels.

In short, being ineligible for 4 cycles of chemotherapy but eligible for up to 9 cycles of EV and 17 cycles of pembrolizumab is somewhat counterintuitive. The toxicity results are highly anticipated.

2) Many questions regarding the study design?

With such study design, many questions – similar to those seen in other neo/adjuvant trials – are, and may remain, unanswered:

What was the rationale for the chosen duration? In a recent paper, we showed that these durations are largely arbitrary (see here).

What is the relative contribution of the neoadjuvant versus the adjuvant component?

What is the relative contribution of each compound?

Why did the study not incorporate a biomarker-driven component, such as ctDNA or other biomarkers, to address these questions?

3) The hope for post-protocol data.

At the last ESMO meeting, the NIAGARA trial – another study in the perioperative setting of bladder cancer – was presented, showing a survival benefit. Post-protocol data were unavailable. Yet such data are essential for interpreting survival results.

Why? Because, as shown in the EV-302 trial, EV–pembrolizumab is the best available treatment for patients with metastatic recurrence. However, in globally conducted trials such as KEYNOTE-905, patients in the control arm may not have access to optimal care upon relapse (EV–pembrolizumab, or even immunotherapy). If this occurs, any observed survival benefit with the experimental therapy may be inflated—or even entirely created.

My primary hope is that post-protocol data will be, at least, reported. Without them – or if they do not reflect current best practice – it will be impossible to know whether the reported benefit would truly replicate in countries with full access to optimal care for patients who recur.

If you want to go deeper about this key topic, see our recent paper here, and the NIAGARA discussion here.

4) Excess dropout among patients “declining” cisplatin?

Last but not least: not only patients “ineligible for cisplatin-based chemo” were included, but also those “declining cisplatin-based chemo”.

How many such patients were there?

It is possible that investigators, in some situations, may have proposed the trial to patients with the hope that they would be assigned to the new EV–pembro regimen. This may have led to the enrolment of some patients who would have received cisplatin had the trial not been open. Now those patients are on “observation” which is not appropriate care for them: they may drop out early to seek appropriate care outside the trial. This can result in frailer patients remaining in the control arm, leading again to the creation – or amplification – of a benefit in the experimental group.

I’m eagerly looking forward to seeing the data and hopefully getting answers to those questions before concluding this is a new standard of care. If you’re around, I hope to see you in person at ESMO in Berlin!